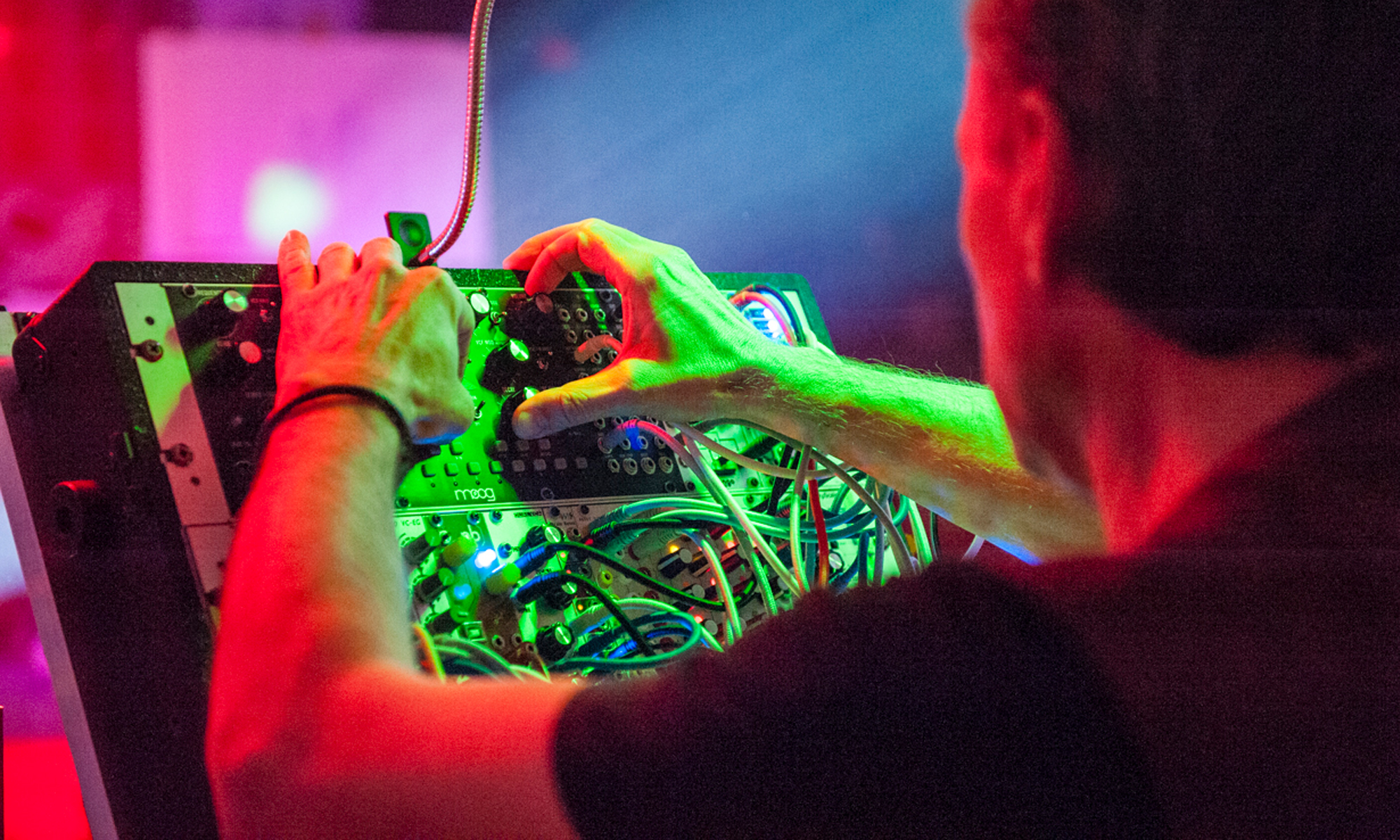

This page is created to use as a Electronic Music Knowlegde Base (EMKB) guideline for those who want to teach or learn arranging electronic music as a producer, musician or DJ without any musical knowledge: this means that this guideline is narrowed down do the most essential basics understanding about scales, chords, chord progression, BPM, till song structures.

This page is created to use as a Electronic Music Knowlegde Base (EMKB) guideline for those who want to teach or learn arranging electronic music as a producer, musician or DJ without any musical knowledge: this means that this guideline is narrowed down do the most essential basics understanding about scales, chords, chord progression, BPM, till song structures.

This guideline will grow along the road by adding new topics and by replying on readers comments: when applicable links are provided to dive deeper into a subject. So keep in mind, this isn’t a complete music theory guide line, it’s to get you started & inspired.

“Don’t Wait To Create”.

Wonna jump to a specific subject just hit one of the content links below or jump back to the “Electronic Music Knowledge Base“.

Content

Introduction

History

Octave

Frequencies

Tuning A440

Writing

Scales

Sharp and flat

Major scales

Minor scales

Other scales

Chords

Major chords

Minor chords

Diminished chords

Augmented chords

Sharp and flat continued

Chords progression

Chords progression scheme Major keys

Major C key chords

Chords Motion Major Key

Chords progression scheme Minor keys

Minor A key chords

Chords Motion Minor Key

BPM

Introduction

How this guide works:

- Subject in bold writing.

- Basic information about subject.

- Images that support the basic information.

- Sometimes (internal) links to more (in depth) information.

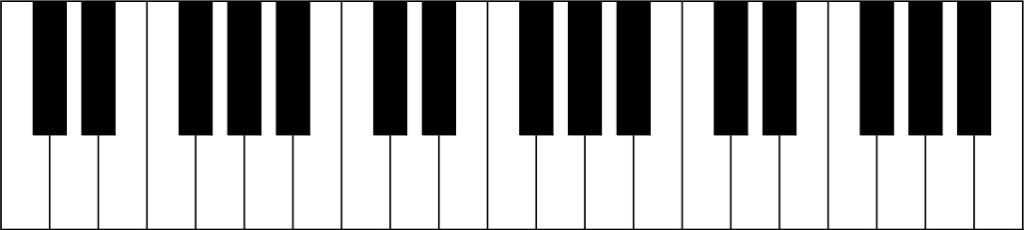

Since most producers work with a DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) and a keyboard controller examples are based on and visualised by using a traditional piano keyboard lay out.

Screen prints of digital workflows will be based on Ableton the DAW used by SONICrider: examples can be easy translated to any other DAW.

History

Note: don’t get confused reading the following paragraphs, all mentioned typical words will be explained later on.

Western music from the Middle Ages until now is based on the diatonic scale and the unique hierarchical relationships created by this system of organizing seven notes.

Any sequence of seven successive natural notes such as C–D–E–F–G–A–B and any transposition is a diatonic scale. Modern musical keyboards are designed so that the white notes form a diatonic scale, though transpositions of this diatonic scale require one or more black keys.

A diatonic scale has five whole steps (whole tones) and two half steps (semitones) in each octave, in which the two half steps are separated from each other by either two or three whole steps, depending on their position in the scale (more about steps/semi-tones which are intervals later on).

Note: in this guide line all scales refer to diatonic scales.

Octave

In music, an octave or perfect octave is the interval between one musical pitch and another with half or double its frequency. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon which is “common in many musical systems”.

The interval between the first (fundamental pitch, the lowest frequency) and second harmonics of the harmonic series is an octave. Two notes separated by an octave have the same letter name and are of the same pitch class.

Frequencies

In music theory, the first octave, also called the contra octave, ranges from C1 (about 32.7 Hz) to C2 (about 65.4 Hz) in equal temperament using A440 tuning. This is the lowest complete octave of most pianos. Based on this first octave the frequencies of the octaves on A are: A1 = 55 Hz | A2 = 110 Hz | A3 = 220 Hz | A4 = 440 Hz | A5 = 880 Hz | A6 = 1.760 Hz | A7 = 3.520 Hz | A8 = 7.040 Hz.

Note: Hz stand for hertz (cycle per second), 1.000 Hz can also be written as 1 kHz (kilohertz).

Tuning A440

In this guideline A440 tuning is the base of mentioned frequencies (and tones).

There’s been a debate floating around about whether instruments sound better tuned to 440 Hz or 432 Hz. While 440 is the standard tuning (and what the vast majority of songs today are tuned to) there are arguments that 432 is a better, fuller, more natural tuning. For this guideline we stick to the A440 tuning.

How to tune a DAW and a modular set up? Transmit/play a A4 tone to your VCO (use a sine wave without any filters applied), route the output of the VCO to an external input in your DAW and insert a tuner with a Hz setting applied: when the tuner hits 440 Hz the VCO is tuned into a A4 (repeat this for all of your VCO’s).

Note: the A above middle C (which is A4) is a relatively centrally-located pitch, accessible to a wide range of instruments.

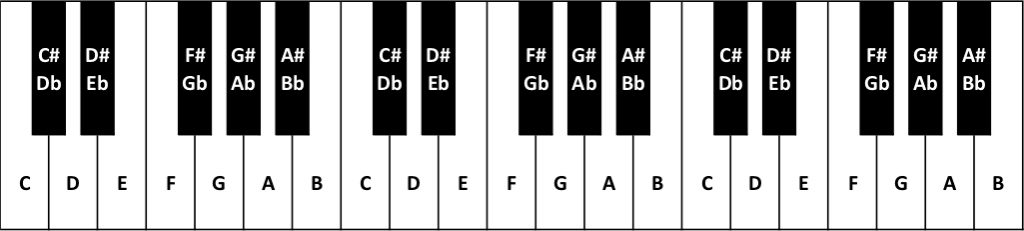

Writing

In writing, a specific octave is often indicated through the addition of a number after the note letter name. The middle C is “C4”, because of the note’s position as the fourth C key on a standard 88-key piano keyboard, while the C above is “C5”, in a system known as scientific pitch notation.

Note: a 88 key piano lowest key is the A0 and the highest key the C8.

Scales

The most important musical scales are typically written using eight notes, and the interval between the first and last notes is an octave.

For example, the C major scale (later on more about major scales) is typically written C D E F G A B C, the initial and final C being an octave apart. In this type of scales there are 8 tones where the first and the last are a perfect eight = an octave (an interval of 12 semitones).

This C major scale uses only the white piano keys.

Sharp & Flat

The black keys have 2 names, both names serve another purpose: for example a C# (C sharp) is a C one semitone higher and a Db (D flat) is a D one semitone lower). Don’t be confused: this part will be clear when talking about chords later on.

Note: many producers use only the # sign, technically spoken this is OK (everybody knows which key need to be played); in musical theory a C# and Db are different notes (although the pitch is the same).

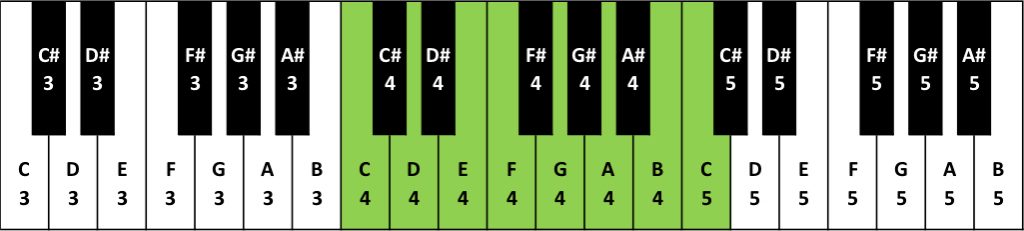

Major scales

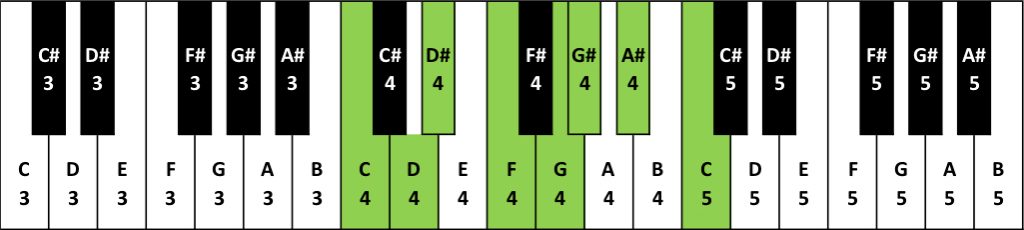

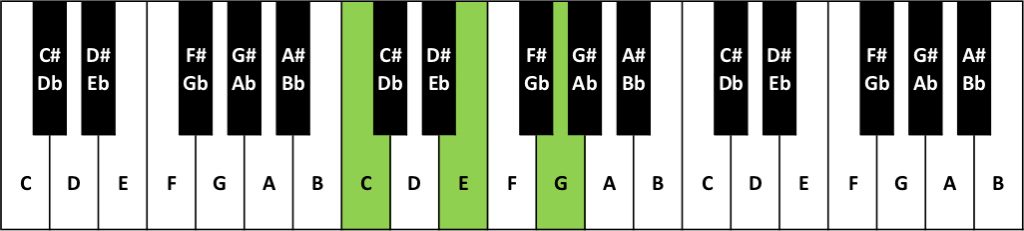

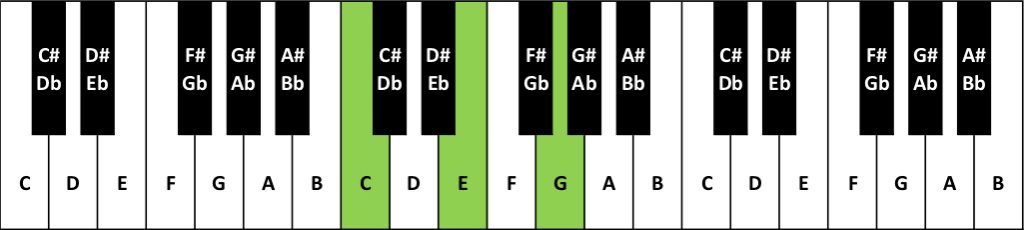

A major scale has certain pre-defined intervals. When we look at the major C scale (C D E F G A B C) we can determine the intervals: this is done by counting the keys between the tones in the octave. In the image below we use the C major scale starting at C4 (green keys) and count the number of semi-tones between notes in the scale.

Starting at C4 there are 2 semi-tones (2 keys) before we reach D4, this means the interval is 2 x 1/2 tone = 1 whole step which equals 1 tone. From D4 to E4 the interval is also 1 tone. From E4 to F4 the interval ½ equals a semitone. Counting all intervals up to C5 give the intervals for the C major octave are: 1 – 1 – 1/2 – 1 – 1 – 1 – 1/2 (in writing: C4 D4 E4 F4 G4 A4 B4 C5), these intervals are applicable for all major scales.

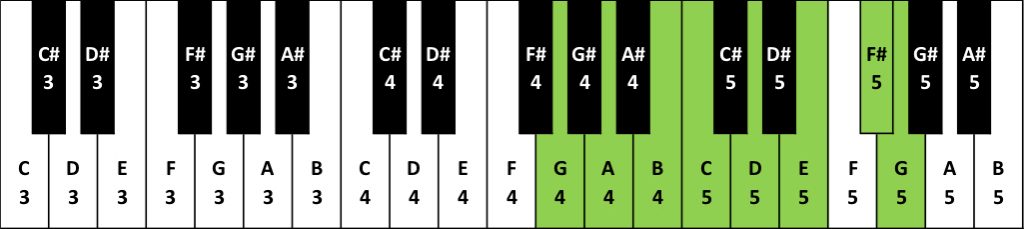

Since the intervals we just figured out apply for all major chords we can determine the major scale for all keys by counting: 1 – 1 – 1/2 – 1 – 1 – 1 – 1/2.

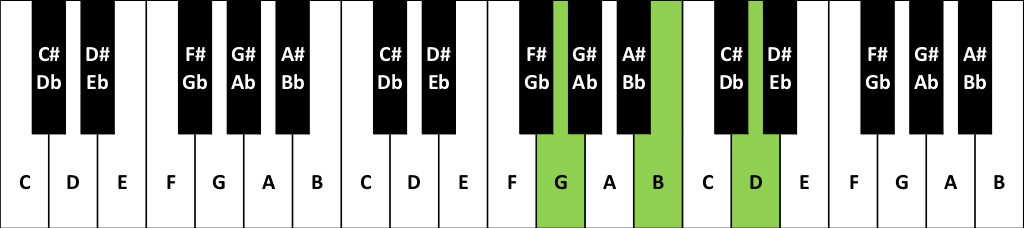

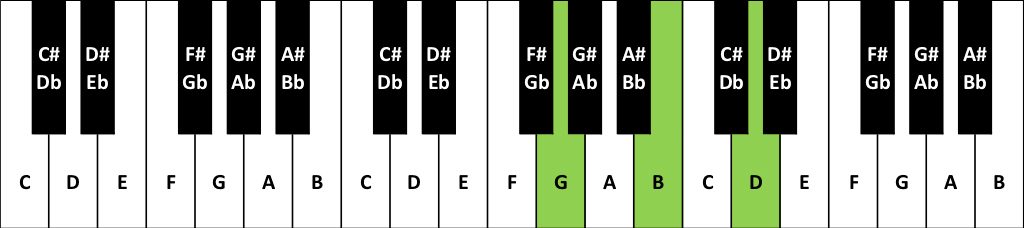

Below the the major scale on G(4): 1 – 1 – 1/2 – 1 – 1 – 1 – 1/2 (in writing: G4 A4 B4 C5 D5 E5 F#5 G5).

Minor scales

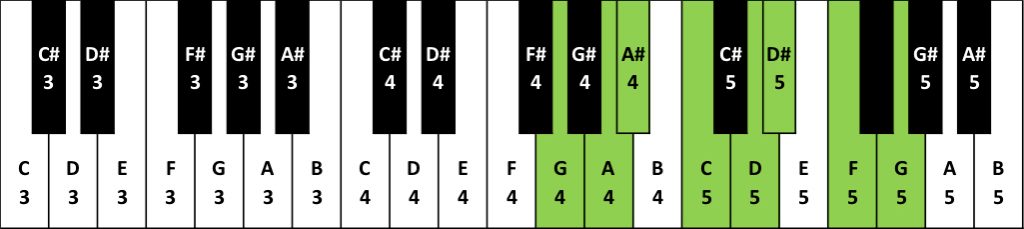

The minor scale is another scale type (frequent used in electronic dance music) which has also certain pre-defined intervals: 1 – 1/2 – 1 – 1 – 1/2 – 1 – 1 (= 12 semi-tones).

Minor scale on C4 = C4 D4 D#4 F4 G4 G#4 A#4 C5

Minor scale on G4 (in writing) = G4 A4 A#4 C5 D5 D#5 F5 G5

Other scales

There are many other scales, but the main idea is always the same: a defined sequence of tones and semitones (intervals), and from this we can create a scale starting with the note we want.

In this guide line we will stick to major and minor scales.

Chords

A chord is any harmonic set of pitches consisting of two or more (usually three or more) notes that are heard as if sounding simultaneously. For practical and theoretical purposes, arpeggios and broken chords, or sequences of chord tones, may also be considered as chords.

Note: chords and sequences of chords are frequently used in modern West African, Oceanic music, Western classical music and Western popular music; yet, they are absent from the music of many other parts of the world.

The most frequently encountered chords are triads, they consist of three distinct notes: the root note (determined by the name of the scale) and intervals of a third and a fifth above the root note.

Note: in this guide line we will investigate – to start with – the four most common chord types. Lets have a look how this works.

Major chords

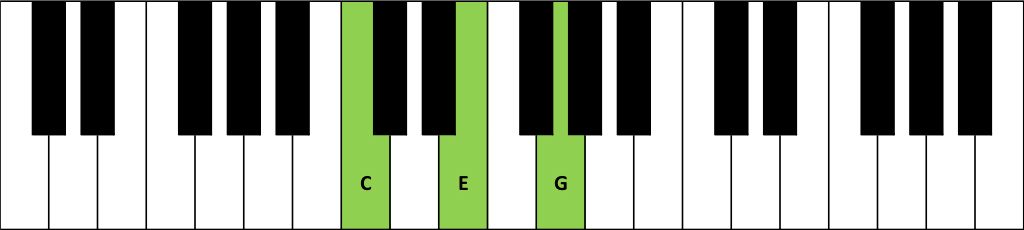

Major chords sound full, resolved and complete. Major chords are built by adding the intervals of a major third and perfect fifth above the root. The root, by the way, is the starting note of the chord (in this example our root is C).

The major third interval is the distance between the root and the note four semitones above it. Since C is our root, E is the note a major third above.

For the third note, the perfect fifth is seven semitones above the root. So in our example, this would be the distance between C and G. Put all this together, and you’ll get a C major chord.

– The root (note): C.

– Major third: four semitones, C to E.

– Perfect fifth: seven semitones, C to G.

Minor chords

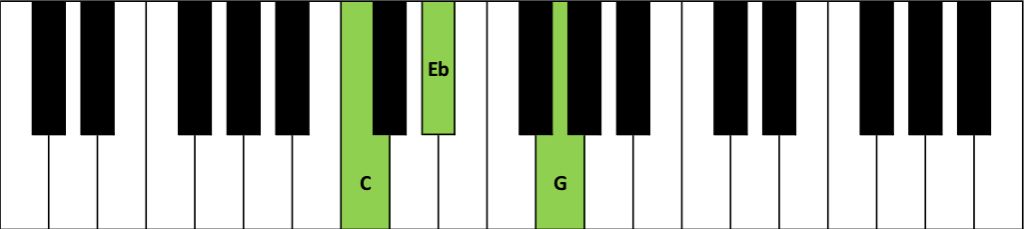

Minor chords sounds a universe away major chords, but there’s only one note of difference. They’re used to bring all sorts of different emotions in music.

Minor chords are built by adding a minor third (three semitones) and perfect fifth above the root.

– The root (note): C.

– Minor third: three semitones, C to Eb.

– Perfect fifth: seven semitones, C to G.

Note: second note in this minor C chord is written Eb, this is “E flat”, which means (as mentioned earlier) one semitone lower. Based on the major C chord – where the second note was an E, in this C minor chord the E should be played one semitone lower, in the correct way of writing this is “Eb”.

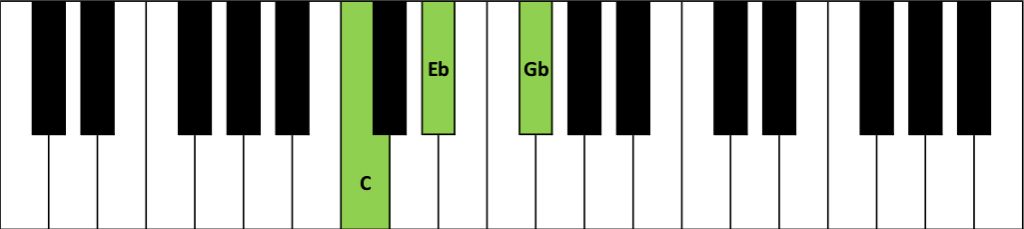

Diminished chords

Diminished chords will add a tense, dissonant sound to your music.

Diminished chords are built by adding a minor third (same as in the minor chord) and tritone above the root. A tritone is comprised of six semitones.

– The root (note): C.

– Minor third: three semitones, C to Eb.

– Tritone: six semitones, C to Gb.

Note: third note in this diminished C chord is written Gb, this is “G flat”, which means (as mentioned earlier) one semitone lower. Based on the major C chord – where the third note was an G, in this C diminished chord the G should be played one semitone lower, in the correct way of writing this is “Gb”.

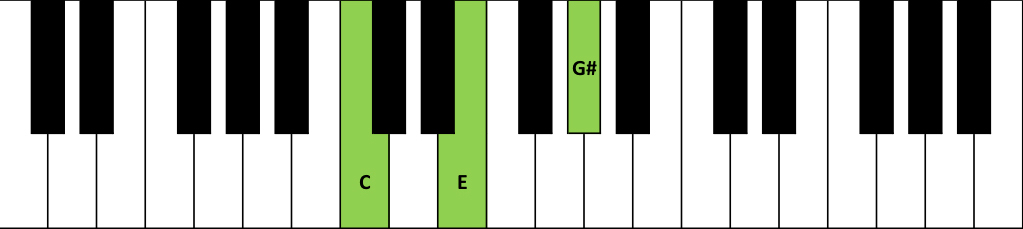

Augmented chords

Augmented chords sound odd and unsettling like something from the soundtrack of a science fiction movie.

Out of all the basic chords, the augmented is the most rarely heard in music. Augmented chords are built just like simple major chords but with an added raised fifth.

The C major chord features the notes C, E and G, so the augmented C chord features C, E and G#.

– The root (note): C.

– Major third: four semitones, C to E

– Raised fifth (or minor sixth): eight semitones, C to G#

Note: third note in this augmented C chord is written G#, this is “G sharp”, which means (as mentioned earlier) one semitone higher. Based on the major C chord – where the third note was an G, in this C augmented chord the G should be played one semitone higher, in the correct way of writing this is “G#”.

Sharp and flat continued

Since this guideline is called “Electronic Music Basics” from now on – in visual presentation of the keyboard – the black keys will have both – sharp and flat – “names”. Where writing the right names – based on the root note – will be used.

Chords progression

Note: the next text can be a bit overwhelming, just read it and in the next chapters it will be breaked down into pieces. When you come back here – after reading all “pieces” – you will noticed you learned a lot.

An ordered series of chords is called a chord progression. Although any chord may be followed by any other chord, certain patterns of chords are more common in Western music, and some patterns have been accepted as establishing the key (tonic note) in common-practice harmony–notably the movement between tonic and dominant chords.

To describe this, Western music theory has developed the practice of numbering chords using Roman numerals which represent the number of diatonic steps up from the tonic note of the scale.

Note: with a good chord progression as your base, other elements of your track, like lead melodies or basslines, become much easier to come up with based on the chords you’ve chosen and where they sit.

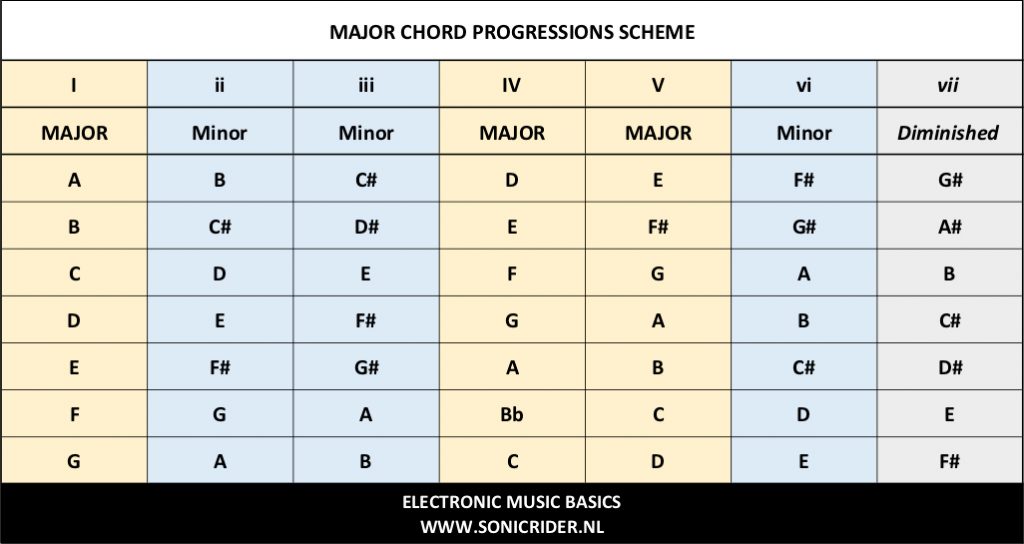

Chords progression scheme Major keys

The image below is the major chord progression schema. Major refers to major octaves (intervals: 1 – 1 – 1/2 – 1 – 1 – 1 – 1/2).

Lets break down the scheme:

Rows:

– Title (1st row) = self explainable.

– Roman numerals (2nd row): the seven basic chords in a chord progressions.

– Chords names (row 3 till 9): the root key of the chord.

Columns:

– Yellow: major chords (I, IV, V).

– Blue: minor chords (ii, iii, vi).

– Grey: diminished chords (vii)

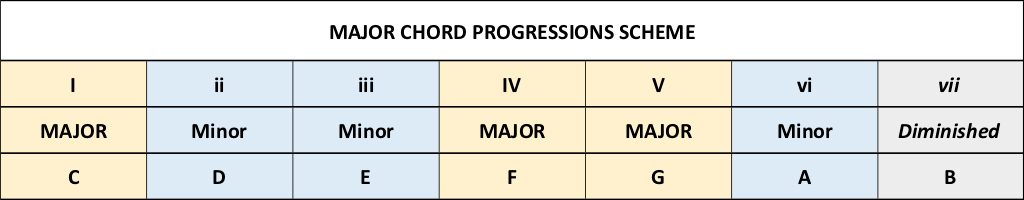

So how do scales & chords come together? In the image below the chord progression scheme for C major octave only.

The C major octave notes are: C D E F G A B C and all basic chords (major, minor and diminished) use the same names: these chords only use the notes in the C major octave. As learned earlier intervals are important in octaves and chords, they meet each other here.

Chord “I”, major C = C E G. Why? Counting the intervals between the 3 notes tells us C to E are 4 semitones and C to G are 7 semitones (see major chord).

What about chord “II”, that can’t be a major chord, based on the major chords intervals the 2nd note would be F# which isn’t part of the C major scale. Therefor chord “II” is a minor chord, more specific a minor D chord = D F A, Counting the intervals tells us D to F are 3 semitones and D to A are 7 semitones (see minor chord).

TIP: try to figure out the intervals for chord “iii” till “vii” and why they are major, minor or diminished.

Can’t figure out these chords? No problem, in the next chapter the chord progression on C major are visualised.

Major C key chords

The images below show all chord for the major C octave, play them on a keyboard (or use a DAW sequencer) and listen the vibes, tention, emotion they spread. To get familiar with major, minor and diminished for each chords the intervals are given.

I MAJOR C (tonic/key note)

– The root (note): C.

– Major third: four semitones, C to E.

– Perfect fifth: seven semitones, C to G.

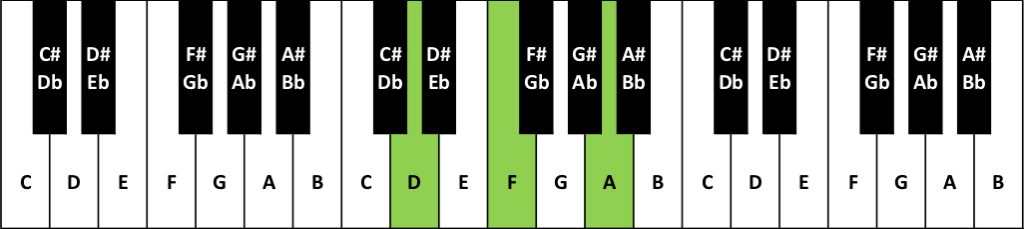

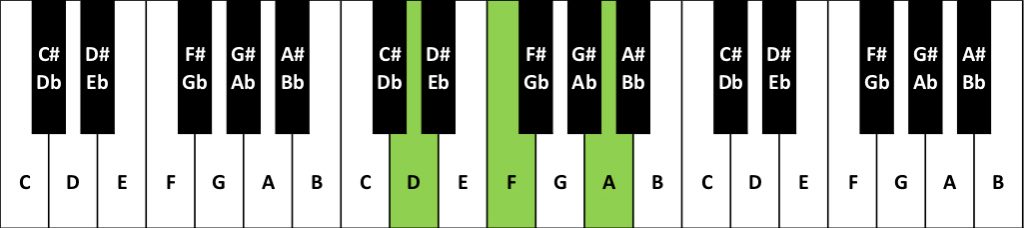

ii minor D (subdominant)

– The root (note): D.

– Minor third: three semitones, D to F.

– Perfect fifth: seven semitones, D to A.

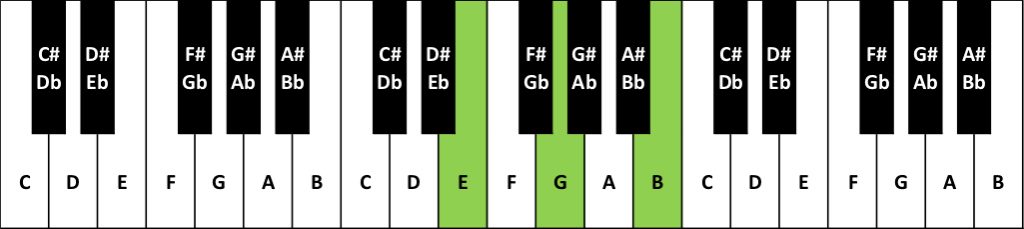

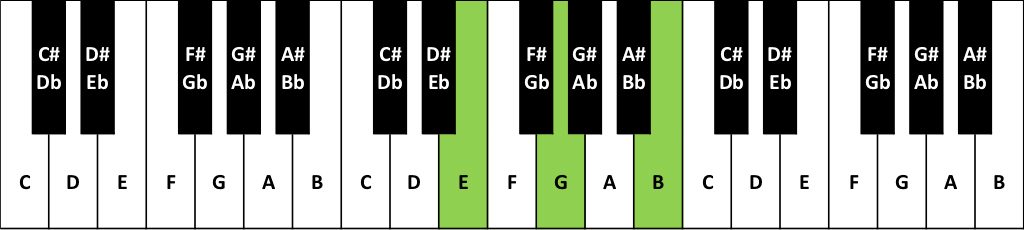

iii minor E (tonic)

– The root (note): E.

– Minor third: three semitones, E to G.

– Perfect fifth: seven semitones, E to B.

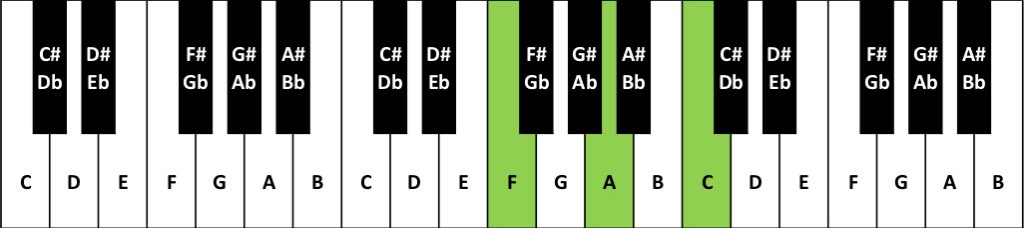

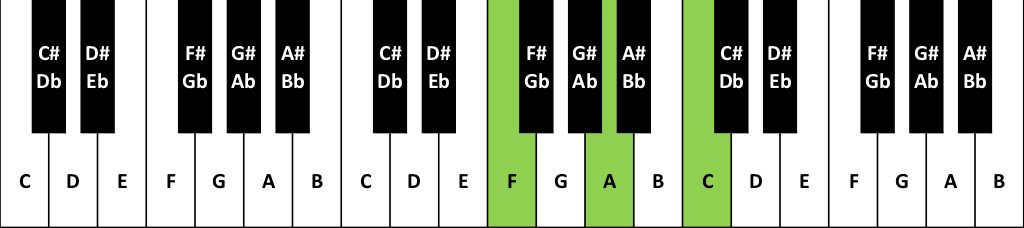

IV MAJOR F (subdominant)

– The root (note): F.

– Major third: four semitones, F to A.

– Perfect fifth: seven semitones, F to C.

V MAJOR G (dominant)

– The root (note): G.

– Major third: four semitones, G to B.

– Perfect fifth: seven semitones, G to D.

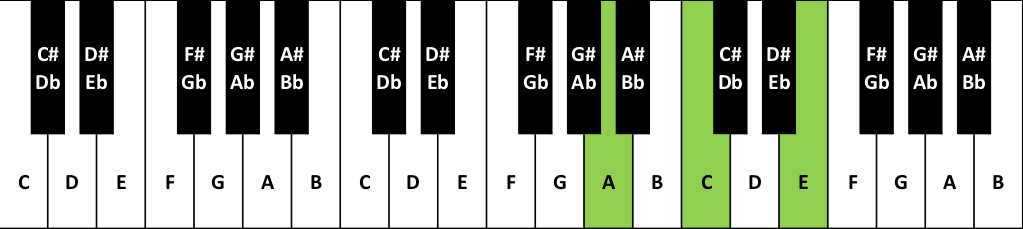

vi minor A (tonic)

– The root (note): A.

– Minor third: three semitones, A to C.

– Perfect fifth: seven semitones, A to E.

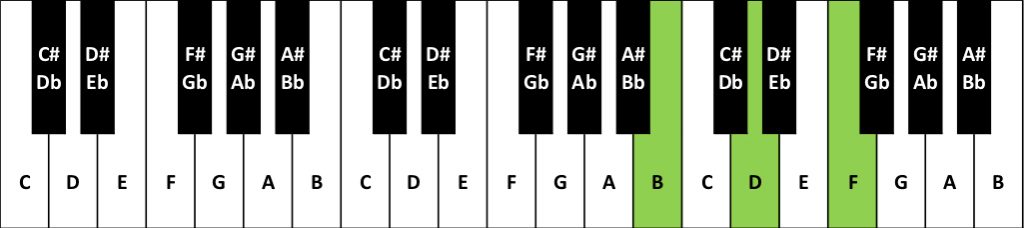

vii diminished B (dominant)

– The root (note): B.

– Minor third: three semitones, B to D.

– Tritone: six semitones, B to F.

Need all the Major Key Triads Chords?? Find them here in a printable PDF.

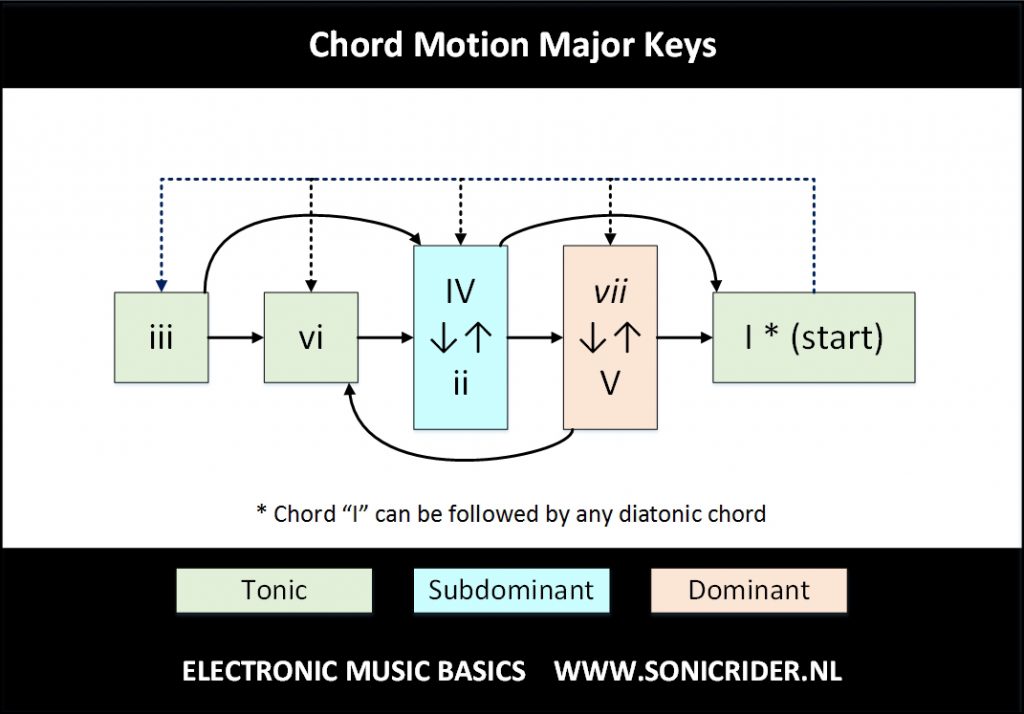

Chords Motion Major Key

We can capture all optional chords motions that “sound good” in a “chord motion diagram”. This diagram helps us to understand motions between chords and the option to create new arrangements.

Chord progressions are what gives a piece of music its harmonic movement; creates the feeling of movement and change. Some chord combinations sound uplifting, others sound somber, and some sound like ocean waves. While these harmonies and how we interpret them are nearly endless, there is a very simple principle at work.

Most pieces of music tend to first establish a feeling of stability, depart from it, create tension, then return to the feeling of stability. Tonic chords create “stability”, subdominant chords “depart from it” and dominant create “tention” (and start again).

Some examples of Major key chord progressions:

– I > IV > V

– ii > V > I

– I > V > vi > IV

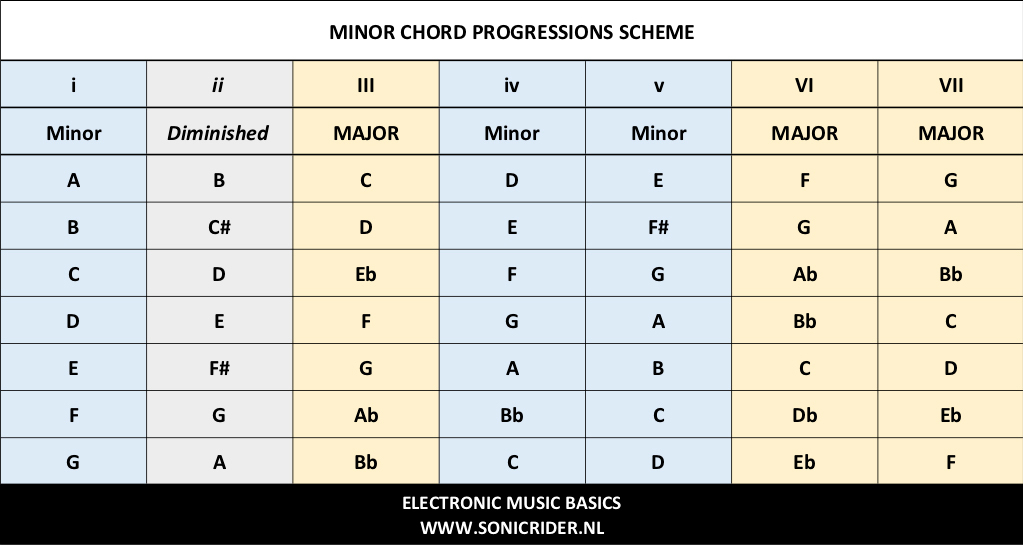

Chords progression scheme Minor keys

The image below is the minor chord progression schema. Minor refers to minor octaves (intervals: 1 – 1/2 – 1 – 1 – 1/2 – 1 – 1).

Lets break down the scheme:

Rows:

– Title (1st row) = self explainable.

– Roman numerals (2nd row): the seven basic chords in a chord progressions.

– Chords names (row 3 till 9): the root key of the chord.

Columns:

– Blue: minor chords (i, iv, v).

– Yellow: major chords (III, VI, VII).

– Grey: diminished chords (ii)

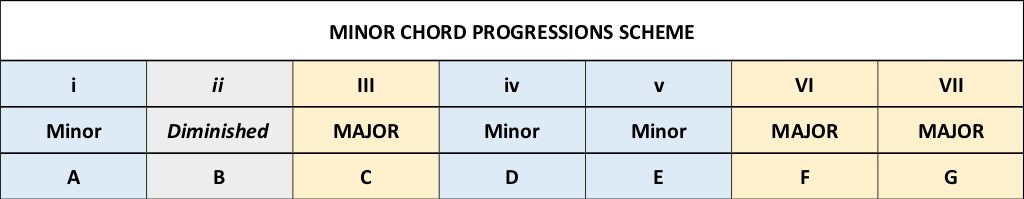

Lets see how minor scales & chords come together? In the image below the chord progression scheme for A minor octave only.

The A minor octave notes are: A B C D E F G A and all basic chords (major, minor and diminished) use the same names: these chords only use the notes in the A minor octave. As learned earlier intervals are important in octaves and chords, they meet each other here.

Chord “i”, minor A = A C E. Why? Counting the intervals between the 3 notes tells us A to C are 3 semitones and A to E are 7 semitones (see minor chord ).

Chord “II”, diminished B chord = B D F. Counting the intervals tells us B to D are 3 semitones and B to F are 6 semitones (see diminished chord).

TIP: try to figure out the intervals for chord “iii” till “vii” and why they are major, minor or diminished.

Can’t figure out these chords? No problem, in the next chapter the chord progression on A minor are visualised.

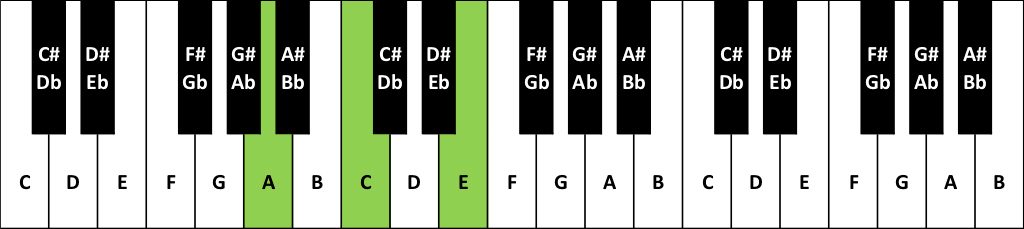

Minor A key chords

The images below show all chord for the minor A octave, play them on a keyboard (or use a DAW sequencer) and listen the vibes, tention, emotion they spread. To get familiar with major, minor and diminished for each chords the intervals are given.

i minor A (tonic/key note)

– The root (note): A.

– Minor third: three semitones, A to C.

– Perfect fifth: seven semitones, A to E.

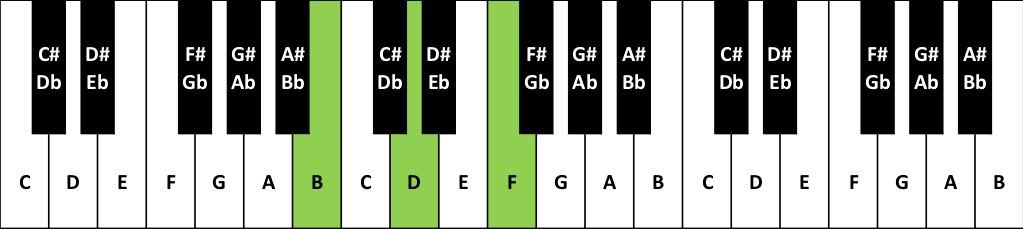

ii diminished B (subdominant)

– The root (note): B.

– Minor third: three semitones, B to D.

– Tritone: six semitones, B to F.

III MAJOR C (tonic)

– The root (note): C.

– Major third: four semitones, C to E.

– Perfect fifth: seven semitones, C to G.

iv minor D (subdominant)

– The root (note): D.

– Minor third: three semitones, D to F.

– Perfect fifth: seven semitones, D to A.

v minor E (dominant)

– The root (note): E.

– Minor third: three semitones, E to G.

– Perfect fifth: seven semitones, E to B.

VI MAJOR F (tonic)

– The root (note): F.

– Major third: four semitones, F to A.

– Perfect fifth: seven semitones, F to C.

VII MAJOR G (dominant)

– The root (note): G.

– Major third: four semitones, G to B.

– Perfect fifth: seven semitones, G to D.

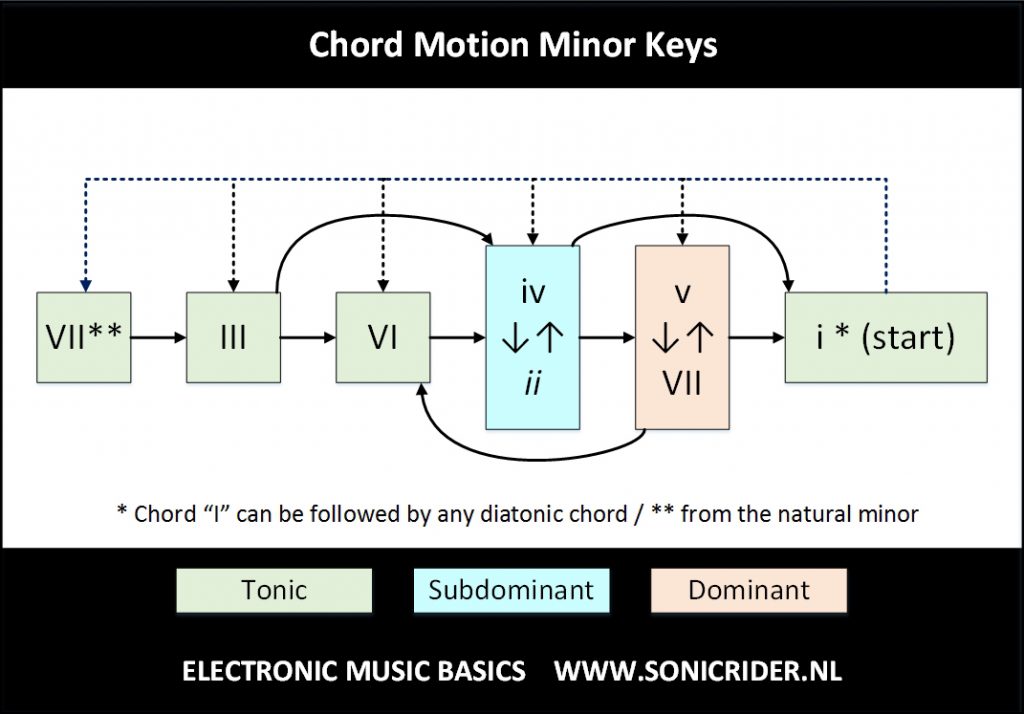

Chords Motion Minor Key

We can capture all optional chords motions that “sound good” in a “chord motion diagram”. This diagram helps us to understand motions between chords and the option to create new arrangements.

Chord progressions are what gives a piece of music its harmonic movement; creates the feeling of movement and change. Some chord combinations sound uplifting, others sound somber, and some sound like ocean waves. While these harmonies and how we interpret them are nearly endless, there is a very simple principle at work.

Most pieces of music tend to first establish a feeling of stability, depart from it, create tension, then return to the feeling of stability. Tonic chords create “stability”, subdominant chords “depart from it” and dominant create “tention” (and start again).

Some examples of Minor key chord progressions:

– i > iv > v

– ii > v > I

– i > VII > VI

As “said” before: there are no real rules in music just tonal mainstream references captured in “well sounding chords motions”. Use the chord progression & motions to experiment in finding your tonal style.

BPM

In classical music, tempo is usually indicated with an instruction at the start of a piece (often using conventional Italian terms). Tempo is usually measured in beats per minute (bpm).

In modern classical compositions a “metronome mark” in beats per minute may supplement or replace the normal tempo marking, while in modern genres like electronic dance music, tempo will simply be stated in bpm. For example, at 120 BPM there will be 120 beats (quarter notes) in one minute, when the time signature is 4/4.

Some of the basic tempo markings:

– Largo is 40-60 BPM

– Larghetto is 60-66 BPM

– Adagio is 66-76 BPM

– Andante is 76-108 BPM

– Moderato is 108-120 BPM

– Allegro is 120-168 BPM

– Presto is 168-200 BPM

Electronic music styles and BPM:

– Dubstep 70 to 100 (mostly 80-90)

– Hip Hop is around 80-115

– Triphop / Downtempo around 90-110

– House varies between 118 and 135

– Techno 120-160 (generally around 120-135)

– Acid Techno 135-150

– Trap is around 140

– Hardstyle is around 150

– Juke/Footwork is around 160

– Drum and Bass averages of 160-180

– Oldschool jungle is around 160-170

– Drum & Bass, Drumstep and Neurofunk 170-180

Thanks for vsiting “Electronic Music Basics” by SONICrider… Hope to see you back since new topics will be added on regular basis; “Don’t wait to create”.